Monday, January 26, 2015

A Recent Correspondence Game

This is a correspondence game I recently played on Chessworld.net.

The final position is very similar to the Damiano's mate I give in an earlier post.

Saturday, January 24, 2015

Thoughts on Opening Repertiore Choices

Why have a specific opening repertoire?

- To specialize in a limited set of openings

- To minimize the amount of study required

Why have I chosen to have to have 2 sets of opening choices?

- Because my objectives differ when playing higher or lower rated opponents

- To get exposure to a larger set of opening ideas and positions

- To avoid boredom and stagnation

- To have a back-up plan in case my opponent is prepared for my opening

Objectives against higher rated players.

- To paraphrase Simon Webb - The tiger must lead the elephant into the swamp.

- Maximize my tactical chances

- Unclear / dynamic positions

- Drawish lines OK – especially forcing tactical lines

- All pawn structures, including IQP

- Stay in book. I want them to leave book worried about my prepared lines.

Objectives against lower rated players.

- The tiger waits for the rabbit to make a mistake

- Minimize my opponent's tactical chances

- Strategically sound positions

- Avoid drawish lines

- Avoid symmetrical pawn structures

- Avoid pawn weaknesses

- Get them out of their prepared lines.

Thursday, January 22, 2015

Chess Graphs: Risk vs. Reward

How to play against lower rated players

I have been given conflicting advice on how to play lower rated players. On the one hand, a strong master told me I should play the sharpest tactical opening lines, and try to blow my lower rated opponent out of the water as quickly as possible.

On the other hand, I get this advice from the book Chess for Tigers by Simon Webb.

"Do you know how Tigers catch Rabbits? Do they rush after them and tear them limb from limb? Or do the stalk them through the bush before finally creeping up on them when their resistance is low?"

My personal experience has lead me to believe the 2nd approach makes more sense. When I play complicated forcing moves against my lower rated opponents, I often just put them in a position where they must find the one move that doesn't lose, and they sit there until they find it. In effect, I am forcing them to play good moves. When I play less forcing moves (still strong moves, just less forcing) I sometimes give my lower rated opponents more chances to make positional errors that I can exploit later.

Now for the Graphs

Imagine if I were to make a scatter plot of chess games. On the x axis would be a measure of the risk involved in the chosen moves (I'm not sure how I would measure this, but sacrifices and gambits would be on the high end of the scale). On the y axis would be a measure of the outcome of the games, from loss to win, perhaps measured by computer evaluations of the final positions.

That graph might look something like this:

For two equally rated players, I would expect all of the data points to fall between the two dashed lines. Notice that when neither player takes much risk, a draw is a likely result. As either player increases the risk, however, the chance of a win or loss increases.

Now consider games where one player is much higher rated than the other. By much higher rated, I mean at least 200 rating points higher (you would expect the higher rated player to score 75% ). I expect the shape of the points to be about the same, just shifted higher.

Looking at this graph, I would conclude that the higher rated player has almost no chance of losing the game if the risk level stays low. As the risk level increases, the chances of winning increase slightly, but so do the chances of losing.

There is a phrase used by strong players when referring to a situation where one player is controlling the risk level of the game in order to avoid a loss. They say the player is "playing for 2 results." Those results being a win or a draw. If there is some risky play (a sacrifice perhaps), the player is "playing for all 3 results."

How to play against higher rated players

So if the higher rated player wants to minimize the risk involved, the opposite must be true for the lower rated player. Looking at the graph, it appears the only chance the lower rated player has is to maximize the risk level.

Once again, I quote Simon Webb:

"The basic principle is to head for a complicated or unclear position such that neither of you has much idea what to do, and hope that he makes a serious mistake before you do. Of course you are still more likely to lose than to win, but by increasing the randomness of the result you are giving yourself more chance of a 'lucky' win or draw."

He then gives some pointers for increasing the risk level against higher rated players. (I am paraphrasing):

- Choice of Opening - Sharp theoretical lines and gambits.

- Play actively- Aggressive attacking play, even if that means sacrificing a pawn or two.

- Randomize - Create unclear and unbalanced positions; complications that can't be figured out over the board.

- Don't swap everything off - Strong players are better in the endgame, so keep the pieces on the board and stay in the middle game.

- Be brave - Your opponent is higher rated so you have nothing to lose.

Conclusion

My tournament experience has convinced me that this is the correct advice. Against a lower rated player, I accumulate small advantages and trade down to a winning endgame. My games may last a long time, but I win a very high percentage of them. Against higher rated players, I throw everything I have at them, often in a caveman like style, but I have some nice upsets as a result.

In a future post, I will show how I changed my opening repertoire to take this advice into account.

Monday, January 19, 2015

Types of chess "rules"

As I am reading about chess, I come across many types of advice and information that are called "rules". Here I have classified them into 5 groups. I would like to hear your opinion about this classification and some examples of "rules" that do or do not fit into this classification.

1. Rules of the game. What FIDE calls the Laws of Chess. These are the rules that govern how the pieces move and capture, how castling is performed, pawn promotion, etc. These rules are the same for OTB, correspondence or blitz chess.

2. Tournament rules. These would be rules that govern how pairings are done, the use of the clock, notation requirements, claiming draws, etc. These rules differ according to the type of competition. Correspondence rules differ from OTB and blitz.

3. Rules of strategy. What I am thinking here would be the fundamental rules that guide decisions of strategy. This would include the relative value of the pieces, the advantage of two bishops in an open position, rooks behind passed pawns in the endgame. Rules in this category would be expected to have few exceptions. If they had zero exceptions, and could be assumed to be true without further proof, we would call them axioms. Can anybody give an example of an axiom of chess strategy?

4. Rules of thumb. These would be rules that have so many exceptions that they must be considered only as rough guidelines. Knights before bishops is a good example. Some in this category might be called parables: for example the story of the man who left his inheritance on the condition that his son never captured a b-pawn with his queen.

5. Rules about how to think. Not specifically about strategy, but more about how to manage your own thought processes. Kotov's tree of analysis for example. Or the advice: If you see a good move, look for a better one.

Have I missed any categories of rules? Do you have examples that do not fit into these categories? What are your favorite rules?

How to Lose at Chess - Checkmate Patterns

Checkmate Patterns

Pattern recognition is an important skill for losing at chess. The following examples show checkmate patterns that you can try to emulate in your games. Let us hope your opponent knows these patterns too.

Back Rank Mate

The most common mating pattern occurs when one player leaves the back rank unprotected, and the king has no escape square.

In the diagram below: White to move wins with 1.Qa8#

If you have the white pieces a good way to lose is to make a useless move with your queen, such as 1...Qa7. Then Black wins using the back rank mate pattern with 2...Rd1#.

Damiano's Mate

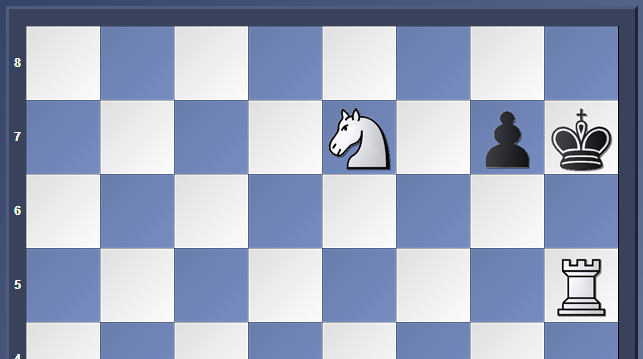

This partial diagram shows the final position of Damiano's mate.

If Black could reach the next position, White could force checkmate in 5 moves. (Hint: Eliminate the rooks with check to get the queen on the h-file.)

If you have the white pieces, you can lose by making a useless move such as 1.Rh2 allowing Black to mate you using Damiano's mate.

Anastasia's Mate

This partial diagram shows the final position of Anastasia's mate.

The following position comes from the novel Anastasia and Chess by W. Heinse in 1803. From this position, White would be able to force mate in 3 moves.

Boden's Mate

This partial diagram shows the final position of Boden's mate.

If Black could reach the following position, White could force mate in 2 moves.

You should try to create positions like this where your opponent can sacrifice a piece to expose your king.

Smother Mate

This partial diagram shows the final position of a smother mate.

If Black could reach the following position, White could force mate in 5 moves.

I will leave it as an exercise for the reader to find a move for White that would allow a back rank checkmate.

How to Lose at Chess - Introduction

How to Lose at Chess - Losing by Checkmate

Sunday, January 18, 2015

How to Lose at Chess - Checkmate in the Opening

Checkmate in the Opening

In the opening, you can increase your chances of being checkmated by failing to develop your pieces off the back rank and by making lots of pawn moves that expose the king. Also, you should never castle if that would make your king safer.

Fool's

Mate

It is possible to be checkmated

in just a few moves. The following example is often called the

“Fool's Mate”.

Notice that by moving his pawns

on the f and g files, White has done an excellent job of exposing his

king to check along the diagonal that runs from e1 to h4. When you

want to lose quickly, move the pawns protecting your king.

Scholar's

Mate

The f7 square is a particularly

weak square right next to Black's king. If you are lucky, White may

try to checkmate you quickly on f7.

Black could have defended f7 by

playing 3...Qe7 or blocked the queen check with 3...g6.

Surely you would not play either of those moves.

Be sure to keep the square f7

unprotected if you want to be checkmated early in the game.

Legal's

Mate

Many players of the White pieces

will not bring their queen out early to attempt the Scholar's mate.

A more sophisticated way to get checkmated is Legal's mate.

Black's move 4...g6 was a

clever losing strategy. Developing a piece by 4...Nc6 or

4...Be7 would have avoided the mate.

Moving pawns instead of

developing pieces in the opening is a good way to get checkmated

early.

Blackburne

Shilling Mate

The story says the master

Blackburne would play amateurs for a shilling a game. He would often

play these moves as Black and usually win quickly.

White did not have

to take the pawn with 4.Nxe5. Greedily grabbing pawns

instead of developing pieces is an excellent technique for losing

quickly.

Notice how in all of

these examples, the losing side did not develop the back rank pieces

and castle. It is usually harder to get checkmated if you castle

early.

How to Lose at Chess - Introduction

How to Lose at Chess - Losing by Checkmate

How to Lose at Chess - Losing by Checkmate

Losing by Checkmate

As beginners, we all learn

that you lose a game by getting checkmated. Later, if you start

playing tournament chess, you learn that you can simply resign a

game, or lose on time. Unfortunately, you may find yourself in a

casual game with no clock, and an opponent who will not accept your

resignation. For situations like this, you will need to learn how to

get checkmated.

There are three keys to

getting checkmated:

- Expose your king to attack along open lines.

- Leave the squares around your king unprotected.

- Limit the number of squares your king can move to.

In future posts

we will use these ideas as we learn about getting checkmated in the opening phase of the game,

typical mating patterns, and as a last resort, checkmates in the

endgame.

How to Lose at Chess - Introduction

How to Lose at Chess - Introduction

I can only imagine why anyone would

want to lose a game of chess. Perhaps you are forced into a

situation where you must play a game against a person of superior

position at work and you dare not win for fear of reprisal. Or

perhaps you will be playing against a relative on their deathbed and

do not want your loved one's last game to be a defeat.

Whatever the reason you want to lose at

chess, I will provide you with all the tools needed to succeed at your

task. You will learn how to get checkmated, how to lose your pieces,

and how to make your position so bad that you cannot avoid loss.

Many of these techniques will allow you to disguise your objective of

losing.

Some have suggested that people may try

to use this information for the exact opposite reason; to try to avoid these

mistakes and improve their game. I find this idea preposterous and

will give it no further consideration.

Topics of future posts to this blog:

- Losing by Checkmate (Checkmate in the opening, typical mating patterns, checkmate in the endgame)

- Losing material (Value of the pieces, blunders, counting, forks, discovered attacks, pins skewers, removing the guard, combinations)

- Positional Mistakes (Weak pawns, weak squares, good and bad pieces)

- Example games

I wish you the best (or perhaps that

should be worst) of luck in your future chess endeavors.

Technical Details - Posting Games

Working out Technical Details

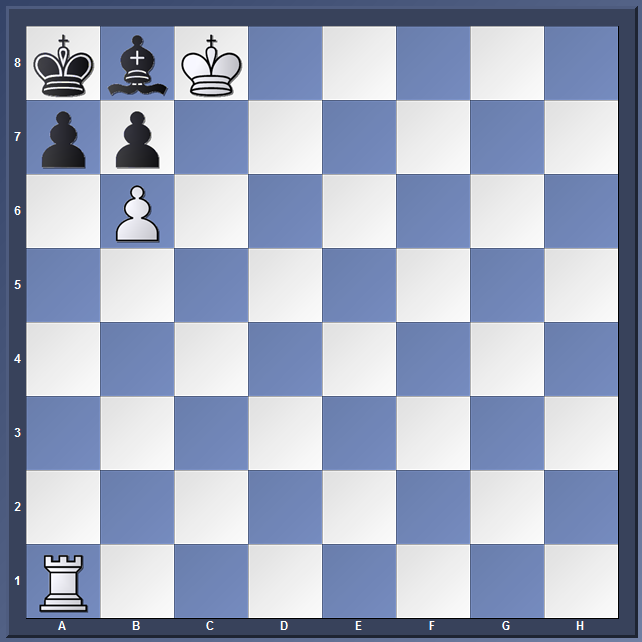

Just making sure I can post games with notes and variations.Practice to see if I can insert a static image of a chess board.

BTW: This problem was composed by Paul Morphy. White to Mate in 2.

Solution to the Morphy Problem:

Welcome to Chess for Engineers

What is this blog about?

This blog is a place where I can share my ideas about chess and chess improvement. The target audience is anyone who is working on improving their chess strength, and those who enjoy thoughtful discussion on a variety of chess topics.Why Chess for Engineers?

In my career I have found that Engineers tend to think differently than people from other professions. Engineers tend to apply more concrete reasoning and analysis, while relying less on intuition and gut feelings. Engineers naturally apply data driven decision making. Engineers are used to explaining difficult technical ideas with precision, and expect others to use similar care in explaining ideas.It is my contention that this manner of thinking translates directly to chess instruction and improvement.

Topic of future posts

Articles (perhaps these might someday be compiled into books)

- Chess for Engineers

- How to Lose at Chess

- Playing Chess Backwards

Other Topics

- Book Reviews

- Opening Preparation and Analysis

- Game Analysis

About the Author

I have a degree in Chemical Engineering from the University of Idaho and have worked as a Process Engineer in the semiconductor electronics industry for over 20 years. Currently I work for SolAero Technologies Corp. manufacturing solar cells used in satellites and other aerospace applications.My USCF rating is currently around 1900, which places me solidly in class A above the 90th percentile of tournament players. So while not a master, I believe I have the strength and experience to be able to give sound advice to improving players.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)